The challenge of ‘under-the-radar’ facilities

In informal settlements, visibility over the standard of care mothers and babies receive at health facilities remains a major gap.

The fragmented health systems in informal settlements include numerous ‘under-the-radar’ facilities, often run by unlicensed providers who may be ill-equipped to support expectant and new mothers, especially when complications develop.

Offering favourable opening hours, medications on credit, and community-embedded providers, unregistered facilities are often a preferential option for mothers, but their quality of care remains questionable.

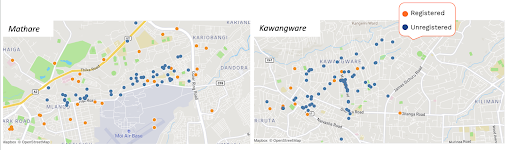

This issue is especially acute in Nairobi’s informal settlements in which 65% of all facilities are unlicensed, many of which lack the essential supplies, resources, equipment, and staffing to meet basic requirements for MNH care.

It has also been demonstrated that a large proportion (22.7%) of women in Nairobi’s informal settlements deliver in a private facility.

Identifying challenges with facility registration

The high proportion of women utilizing private health facilities and the lack of studies exploring the informal provider experience indicated a need for research into the perceptions of registration.

In early 2022, Jacaranda Health engaged unregistered facilities to examine barriers to registration and potential pathways to enhance private facility involvement with the regulatory process.

The process was part of a three-year USAID-funded implementation research project, Kuboresha Afya Mitaani, which aimed at holistically understanding and addressing the complex maternal, newborn and child health challenges in Nairobi’s informal settlements.

Many unregistered facilities have remained “under the radar” to researchers given the sensitivity of admitting their status and fear of legal ramifications or forced closure.

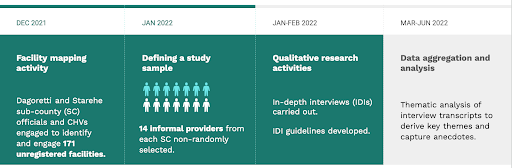

Given the sensitive nature of this research, Sub County representatives advised on Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) as the channel to reach, engage, and build trust with unregistered facilities, who, in December 2021, mapped unregistered facilities across the two informal settlements before capturing basic information from the owners on the facility size, location and contact information (Figure 1).

Between 27th January and 4th February 2022, a scoping study was conducted via 14 key informant interviews with providers from Dagoretti and Starehe, with the aim of:

- Understanding the barriers to registration faced by health providers in informal settlements

- Establishing the willingness of leaders and owners of unregistered facilities to register formally

- Exploring what support unregistered facilities need to achieve registration.

Key timelines for data collection and analysis are included in Figure 2 below.

Results from the qualitative inquiry indicated that unregistered providers were willing to engage in the registration process, (many citing its wider benefits), yet face a number of financial, operational, and professional challenges in achieving formal registration status.

When asked if they felt there were benefits to registration, overwhelmingly, all respondents agreed that registration was a helpful step in being able to provide services to clients.

Respondents felt that achieving registration status gives facilities legitimacy with the government, and with the community. When government inspections occur, some unregistered facilities would close in order to avoid penalisation. With registration, providers noted that they have the security not to close or hide operations, as suggested by one Dagoretti-based informal provider:

“When patients come to the facility and find you closed [because of inspections], they start to doubt your capability of providing services. So, if you don’t close, you get a good reputation and people will refer you to other customers like ‘go to that facility, I don’t see them closing when the inspectors are around.”

Barriers to registration are broken out in the table below:

|

Barrier

|

Challenges for providers

|

Qualitative feedback from informal providers

|

|

Financial barriers

|

(i) Lack of funds to pay the registration fee

(ii) Lack of funds to upgrade facility infrastructure |

With finances, you bring the facility up to the recommended standard […] like having running water and an incinerator to burn waste. We lack financing; that’s why we don’t do things in the right way and cut corners for the sake of registry.” – Respondent 11, Dagoretti

|

|

Operational barriers

|

(i) Corruption/harassment at registration offices

(ii) Lack of information on registration process |

“The officer takes advantage and harasses people like the chemists. They ambush you, and if you fail to give them the money they say they need they arrest you. When the police arrest you, he doesn’t take you to court but instead asks for ksh 10,000.” – Respondent 2, Stahere

|

|

Personnel barriers

|

(i) Lack of personnel qualifications

(ii) Staff shortages + high staff turnover |

“The issue is training. I’m not a lab technician; I am a clinical officer. But to register a clinic, the clinic needs a lab technician. So for the sake of not having to bother with someone, I am forced to work as a lab technician without the qualifications.” – Respondent 3, Stahere

|

Actionable next steps to support informal providers achieve registration

Registration remains a sensitive issue, but it is integral to mothers receiving coordinated, regulated, quality services, and facilities receiving equitable, targeted allocation of resources from health system managers.

Insights from the study could help policymakers and decision-makers improve MNH service provision in informal settlements by better supporting the registration process for informal providers.

Policymakers should consider:

- Reducing the financial barriers to registration, by introducing equitable payment schemes that make the process more financially attainable, and introducing subsidised training to qualify practitioners who operate in informal settlements.

- Introducing clear requirements that minimize bribery and clear communication on the status of the application to make the process more transparent and understandable for all informal providers. Shifting the requirements and registration application system online (versus existing paper-based processes) would offer more transparency and accessibility, and reduce opportunity for corruption.

- Offering equitable training options for informal providers. Achieving the requisite professional degree and the documentation to support this is mandatory for registration, as it enables visibility over the type of provider and regulation of their clinical skills. Our reports indicate that there is a large patient demand, which exceeds the availability of formally qualified practitioners. The county government could increase the pool of trained practitioners by investing in sustainable, scalable programs like MENTORS and its accompanying mHealth tool DELTA that help informal providers earn CPD points and the documentation to qualify for registration and offer quality MNCH services.

- Providing lists of registered facilities to mothers: Community consultations with providers in Year 2 of KAM offered valuable suggestions to empower mothers with information on whether the facilities they visit meet government regulations for care provision: “Since most mothers do not know the difference between registered and unregistered facilities in informal settlements, we could provide that list when they come for ANC, so they are aware.”

What can other implementers working in urban informal settings learn from this?

Formal registration status isn’t necessary to provide care and develop relationships with the community. Therefore, it is important to understand the experiences of providers that are not registered, to support them to enter the formal regulatory system, thus promoting a higher standard of care that is provided to clients.

Dissemination of these findings to policy makers is important as a driver of policy change to make registration more accessible and desirable for providers that have been operating without registration.