The ‘twin challenge’ facing adolescent mothers in informal settlements

In Kenya, adolescent pregnancy is a health and social concern because of its association with higher morbidity and mortality for mother and child and adverse social consequences.

In Nairobi’s informal settlements, these mothers bear a double burden:

- Direct health implications related to difficulties navigating a fragmented health system

- Wider social implications like forced cohabitation, missed education, and social stigma.

These implications, combined with limited access to clinically-accurate information, contribute to poor health seeking behavior.

Between 2020 and 2023, Jacaranda Health and the Nairobi Metropolitan Service (NMS) partnered within a USAID-funded implementation research project – Kuboresha Afya Mitaani – which aimed to tackle complex urban health challenges in two Nairobi informal settlements, Mathare and Kawangware.

The project was underpinned by participatory implementation research approaches to ensure interventions are effective and relevant for mothers, and can be sustained by the community.

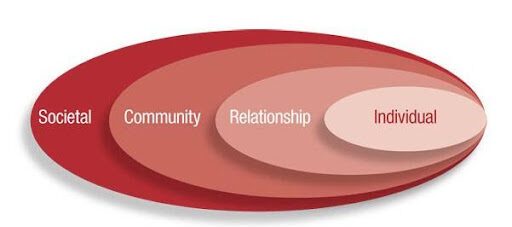

Contextual factors impacting adolescent mothers exist across multiple layers of her surroundings

A series of community consultations conducted as part of the project in 2021 identified two major barriers to care seeking amongst adolescent mothers in these settings;

- Key information gaps around pregnancy, labor and delivery

- An absence of support systems during the pregnancy journey

With support from NMS, Jacaranda conducted qualitative research through focus groups and telephone interviews with adolescent mothers to better understand their lived experiences and barriers to care across multiple social layers, as below.

Using the social ecological model, we organised the data into these categories as the organising themes as outlined below:

1. Individual

Adolescent mothers expressed various emotional challenges, including regret, guilt and shame, as well as various physical or health challenges that they experienced such as “tiredness” and “sickness”.

“I was sickly but convinced myself I wasn’t pregnant. I didn’t know what to tell my parents.”

Having to drop out of school was also identified as a challenge, and this came about either due to challenges breastfeeding, or due to pressure from family members or partners.

“I would go to school and the milk would start leaking and it made me so uncomfortable. I realized all those times I took time away from school to breastfeed was not doing me good. I was missing a lot of lessons, so it was affecting me in terms of academics.”

2. Family

Participants highlighted financial challenges, specifically not having enough money for needs such as food, and also for accessing health care such as maternity or prescribed drugs.

“The baby’s father would leave us in the house without food. I had financial challenges going to the clinic and when I informed him he did not support”.

Participants also expressed having experienced isolation from family. In some cases, they were asked by their parents to leave home, while in others they preferred to relocate. Instances of physical violence from the parent or from their partner were common.

“My dad did not want to be responsible for the pregnancy and asked me to go and be with the one who was responsible for the pregnancy.”

3. Society and school

Participants expressed they experienced stigma in the form of discrimination and disrespect from other community members, as well as people laughing at her.

“I used to feel bad, because out of all my friends I was the only one who was pregnant and then they abandoned me and some were telling me that I didn’t take good care of myself.”

Participants felt isolated from friends and from the community. They also mentioned that some friends were not allowed to be in their company.

“I was afraid of going outside, I used to stay in a flat and so everyone knew that I was pregnant.’

4. Health system

There was a lack of respectful maternity care at the health facility during labor and delivery. Participants expressed having been abused verbally and even physically during the delivery.

“I was in pain. The doctor screamed at me that I was behaving like a fool. She asked me whether I drink alcohol and I told her that I don’t, but she pinched me hard.”

Participants also expressed having experienced lack of respectful maternity care during their antenatal care visits in the form of verbal abuse.

“They were upset that I had started an antenatal clinic very late. They insulted me telling me that ‘our work is just to spread our legs and get pregnant’”.

Addressing barriers to care seeking for adolescent mothers.

The findings were thematically analyzed and helped identify emotional, informational, and primary care-based needs, including the need for a safe space to ask questions and receive information during pregnancy and postpartum, advice on how to claim on free maternity care, respectful, age-relevant care in facilities, and additional support for cases of gender-based violence or abuse.

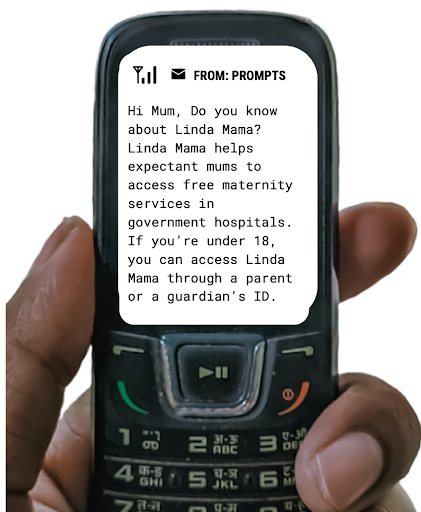

This confluence of factors led to the adaptation of new messaging content on Jacaranda’s digital health solution PROMPTS in 2022 to address specific knowledge gaps.

PROMPTS already empowers women with information and referral support via SMS to seek care at the right time and place, but these findings prompted the development of age-specific content to better plug knowledge and support gaps for these more vulnerable mothers.

Content adaptations included messaging aimed at the caregivers of adolescent mums (who were more likely to own phones and enroll to the platform on their behalf), alongside developing targeted content for the SMS messaging to include targeted information:

- Labor and delivery, given some participants expressed having experienced complications during their delivery while others were not aware of labor signs which in one of the instances led to a more complicated delivery process.

- Accessing Linda Mama, Kenya’s free maternity insurance scheme, which emerged as a challenge. One mentioned that they were unable to access Linda Mama because they were under 18, which may mean they are unaware that the service is available to them if they register via their guardian.

- Referral for emotional supportive services and gender based violence screening, given the number of adolescent mothers who expressed social concerns around stigma, forced cohabitation, and feelings of isolation.

What can other implementers working in urban informal settings learn from this?

Insights from KAM have helped inform Jacaranda’s strategic planning for PROMPTS over the next few years, including content and message delivery adaptations that will target disadvantaged populations, such as adolescent mothers and those with lower SES.

Additionally, high user activity among enrolled mothers and the changes observed in care seeking and knowledge with the newly-adapted messaging under KAM, also suggest that PROMPTS could be used to support other MNCH use cases, including nutrition for children under 1 years of age.

This research and surveys contribute to the growing body of evidence that mHealth and digital health interventions can be adapted to shift behaviours and support pregnant women and new mothers in informal settlements. However, contextually-targeted solutions have more value and relevance with their end user, thus qualitative and quantitative research to understand subgroups and disadvantaged populations and their unique needs should be completed early.