The Context: Kuboresha Afya Mitaani

Approximately half of Nairobi’s population live in informal settlements or “slums.” Access to maternal, newborn, and child health (MNCH) services is more challenging for the urban poor living in these settings because of the low level of education, unemployment, younger maternal age, low social integration and support.

Many of these urban poor come from displaced, refugee, or migrant backgrounds with other socio-cultural taboos which further complicate the care-seeking patterns.

The Kuboresha Afya Mitaani (KAM) project aimed to improve MNCH outcomes for women in informal settlements of Nairobi. The project’s goal was to demonstrate how innovative approaches to tackling complex health challenges in urban settings can be integrated and replicated in other urban health contexts.

Recognizing the importance of participatory approaches to strengthening often-fragmented informal health systems, the study was built around the concept of a ‘Quality Ecosystem,’ integrating typically siloed sectors in the quality of care space and technological innovations around solutions to MNCH challenges that could mutually reinforce one another.

The ecosystem included: (1) Jacaranda Health’s core solutions, PROMPTS and MENTORS, (2) air quality and water and sanitation as environmental health drivers, and (3) development of a participatory multi-stakeholder forum.

Using an implementation research approach, the KAM project tested how best to strengthen the quality ecosystem in two diverse informal settlements in Nairobi County, Kenya – Kawangware and Mathare – where almost 60,000 vulnerable women and children live and the maternal mortality rate is almost twice the national average (362/100,000 live births).Where women seek maternity care has an impact on their health outcomes.

It is widely accepted that seeking care at a facility during the pregnancy and postpartum periods is important to support better health outcomes for the mother and baby.

However, in urban informal settings where the quality of facility-based care varies widely (and is generally hard to regulate), understanding why women seek care at certain facilities can build a deeper understanding of these facilities from the client perspective (cost of services, perceptions of quality, availability of services), and help streamline improvements to higher-volume / preferred facilities.

Literature review demonstrated that few published studies have focused on this care-seeking behavior in urban settings. Some studies have focused broadly on patterns of care-seeking in urban informal settings, but few have disaggregated its influencing factors, such as education and wealth status.

The Question

Previous research done at Jacaranda Health demonstrated that providers in the public facilities report seeing a lack of continuity in their clients. Mothers come to them for antenatal care (ANC), disappear during their delivery period, but then return for postnatal care (PNC). This suggests that some mothers may choose to seek care elsewhere for delivery. This led us to want to understand the patterns of care seeking throughout a mother’s pregnancy and postpartum journey, and delve into possible differences across wealth groups.

Ultimately, we hoped to answer the question: Are mothers who are already at a disadvantage because of their lower wealth status further disadvantaged by where they seek care?

Study Design and Analysis

As a part of the KAM project, we administered an endline household survey to a sample of mothers living within Kawangware and Mathare. A sampling frame was generated through a household listing activity, completed using the help of community health volunteers (CHVs) in collaboration with Nairobi County Department of Community Health, in July 2022 at endline.

CHVs were used, as they were permitted to engage with communities during the COVID-19 pandemic and due to their knowledge of and connection with the community. CHVs helped identify all households within Kawangware and Mathare that housed pregnant women and caregivers of young infants who met the study population criteria (eg, women aged 15-49 years who were currently pregnant or had given birth within the last year). Households were included only if the woman intended to stay in the locality for the next six months.

A total of 8,088 households were listed at endline. A modified Lot quality Assurance Sampling (LQAS) sampling procedure was used. Kawangware was subdivided into four Supervision Areas (SAs) corresponding to the four villages in Kawangware (Kawangware, Kabiro, Gatina, Ngando) while Mathare was subdivided into six SAs (Mlango Kubwa, Hospital, Kiamaiko, Mabatini, Ngei and Huruma). Each Supervision Area (SA) had at least one study health facility.

Households were sampled from each SA. 938 households were sampled and 738 were interviewed. In the interview, women were asked to report where they went for ANC, delivery, and PNC. In addition, we collected demographic information, including wealth.

We then analyzed the patterns of where they sought care across wealth groups. This was done using two-sided t-tests, looking for associations between wealth level (classified as lower and higher wealth) and (1) use of private or public facilities for ANC, delivery and PNC, (2) use of KAM study facilities for ANC, delivery, and PNC, and (3) the amount women paid for delivery.

We also paired the quantitative inquiry with qualitative research, focus group discussions and in-depth interviews with mothers in the informal settlements and providers working in facilities in the informal setting. These interviews were analyzed thematically and used to contextualize the quantitative findings.

Results

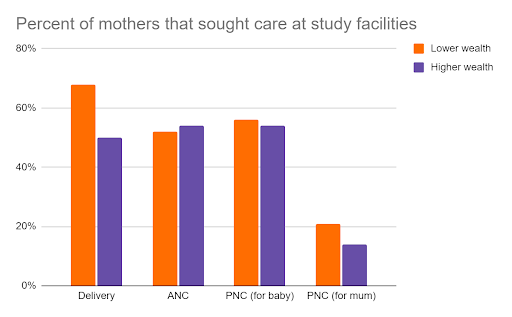

We found that there were significant differences in locations where mothers of different wealth groups sought care for delivery with more women in the lower wealth group (68%) seeking care for delivery in KAM facilities than women in the higher wealth group (50%, p-value = 0.01). There were no significant findings in terms of care seeking during the ANC and PNC periods (note: see full table of data at the end of this blog).

What does this tell us about care seeking behavior of mothers?

1. Mothers prefer the quality of care or perceived quality of care outside of the informal settlements.

Our findings show that there are differences in where mums choose to seek care for delivery, according to their wealth status. Those with more wealth, and therefore more flexibility to choose where to deliver, tended to go to non-KAM facilities. The KAM project included most of the facilities within the informal settlements, therefore this suggests that mums in the higher wealth group chose to leave the informal setting for delivery more frequently than mums in the lower wealth group.

This would suggest that mums prefer the quality of care or the perceived quality of care outside of the informal settlement. This concept of perceived quality is an important one, as it tells us that not only does the actual quality of care drive health seeking behavior, but also the perception of quality is motivating. This has important implications, as improving the perception of quality may help direct health seeking behavior.

2. Private facilities are preferred over public facilities.

We found a tendency to seek care in private facilities amongst the wealthier group (while non-significant). Assuming that those in the higher wealth group have more freedom of choice, it is interesting to see that they choose to seek care in private facilities.

This has been confirmed by other studies which tell us that informal settlement residents tended to go to private facilities over public facilities for health care. Qualitative inquiry with mothers in the informal settlements demonstrated that quality was the most frequent driver of facility selection. As one pregnant woman, 29 years, in Kawangware noted:

“I had to start attending ANC at a private clinic because when you visit the public hospitals, they don’t even check your pregnancy to establish if you and the baby are okay. They just observe you and take your weight …”

However, there is a lot of variation in the quality of care offered at private facilities. Furthermore, in Nairobi’s informal settlements, private un-registered providers frequently offer maternity services, however their quality is unregulated by the government. Therefore, there is a need to understand and regulate the quality of care provided in private facilities.

There may also be value in changing the perception of public facilities, by improving the level of quality and the consistency with which it is delivered. This would shift the perception of the public sector, and it would bolster equity in maternal health care, by ensuring that all mothers, regardless of financial status, receive high quality care when attending public facilities.

It is important to remember, wealth as a driver of decision making is not as straightforward as having money to pay for a private facility. In Kenya, the National Health Insurance Fund (NHIF) covers maternity care for all women under the “Linda Mama” scheme. All pregnant women are eligible to enroll in the program with coverage for basic ANC, delivery, and PNC care at any NHIF accredited facility, public or private.

In theory, this should mean that women have full financial freedom to select where to receive maternity care. However, the wealth-driven trends in care seeking indicate otherwise. The reasons for this are not clear. It is possible that women are not aware of their ability to be covered at private facilities.

This is an opportunity for Jacaranda Health to intervene. PROMPTS, our AI-enabled SMS platform, has the ability to inform mothers of the benefits that NHIF coverage offers them if they enroll. Or perhaps other financial barriers, such as need for transportation to facilities, or need to spend time on income generating activities rather than healthcare, is hindering the ability for women in the lower wealth category to choose where to seek care.

This warrants further investigation, to try and promote more freedom when it comes to facility choice.

3. Mothers frequently change where they seek care during the course of one pregnancy.

The fact that we only found a difference in delivery location, but did not find a significant difference in ANC or PNC location by wealth, suggests that some mothers change facilities during pregnancy, going to different locations for delivery than they do for ANC and PNC. While it’s difficult to speculate on the reason for this, it does mean that we have an opportunity and a responsibility to support continuity of care.

This could be achieved by easing access to medical records, building communication between providers and facility leadership, and more. At Jacaranda, we plan to delve into this in the future, as we understand that promoting continuity of care would help support the mother throughout her pregnancy journey.

Limitations

We acknowledge some limitations to our study, such as small sample size. However, we suggest that these findings be used to drive further research and understanding into the patterns of care seeking for mothers and may prompt a deeper discussion of policy that supports equity and quality of care for all women.