There has been a baby boom at Jacaranda Health, and not just in our partner counties. In the last two years, eleven members of our team have had babies of their own, including four new fathers. And these new fathers started asking: “Why do we only target our SMS program to pregnant women and new moms?” and “Many men are clueless on issues of pregnancy and newborn care, so why don’t we try reaching out to them too?” It was a good point.

The World Health Organization cites male involvement in maternal and newborn health as a key factor in furthering safe motherhood. Yet, perceptions of pregnancy, birth, and childcare as the role of women, and a lack of suitable healthcare infrastructure have led to low participation of men across sub-Saharan Africa. Long queues at health centers may mean that men lose a day’s income if they accompany their partner. Negative treatment by health facility staff and fear of mandatory HIV testing can further discourage male involvement.

Adapting PROMPTS messages for fathers-to-be

We started to explore what male involvement in our SMS program, PROMPTS, might look like, with the goal of increasing male participation in maternal and newborn health issues.

We held focus groups with male partners of pregnant women and new fathers at Kiandutu Health Centre in Kiambu County with 25 men, and also gained key insights from Taji Phillips, a master’s student who spent the summer with us from the Duke Global Health Institute. Taji’s research explored the experiences and perspectives of male partners with infant care and exclusive breastfeeding, drawing participants from the public facilities where Jacaranda Health works.

Through her interviews and story completion activities, and the focus groups run at Kiandutu, we learned that for many men, the main sources of information on pregnancy, birth, and baby care were personal experience and friends/social gatherings. Taji’s research also highlighted a lack of father-centered information at public health facilities. A few men in the focus group confidently shared incorrect information about things like using fundal pressure during delivery or the connection between HIV and exclusive breastfeeding.

Almost all of the men were receptive to the idea of using SMS to get accurate, free information. They mentioned a wide variety of topics they would like to learn about, from how to get a male/female child to handling their partner’s emotions to danger signs after delivery. They also asked for the messages to be complementary to what their female partners receive.

We took a condensed package of key PROMPTS messages and adapted them for their male partners. We kept the information short and focused on critical issues, such as danger signs, since men expressed that they had busy schedules and wanted fewer messages.

We also added new messages on respecting one’s partner (i.e. avoiding physical confrontations and abuse), the importance of a pregnant woman being comfortable/consenting to having sex (even if medically it is not counter indicated), and how men can play a role in newborn care with things like bathing, burping, and changing diapers.

Our in-house nurses reviewed the content for medical accuracy and alignment with Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines. The final pregnancy package for men contained 16 messages delivered over 2 months, and the postpartum package contained 20 messages delivered over 6 months.

Testing our new male-partner messages on PROMPTS

We conducted surveys with ~50 male partners of pregnant women/new mothers in Murang’a and Makueni Counties to get a baseline and allow us to test whether the messages would have any effects on the men’s knowledge and behaviors. To enroll the men, we sent a blast SMS to 12,000 of the women on our platform, inviting their male partners to join the male arm of PROMPTS using unique keywords for the pregnancy or postpartum package. 1,127 men enrolled and we began piloting our first ever male messages.

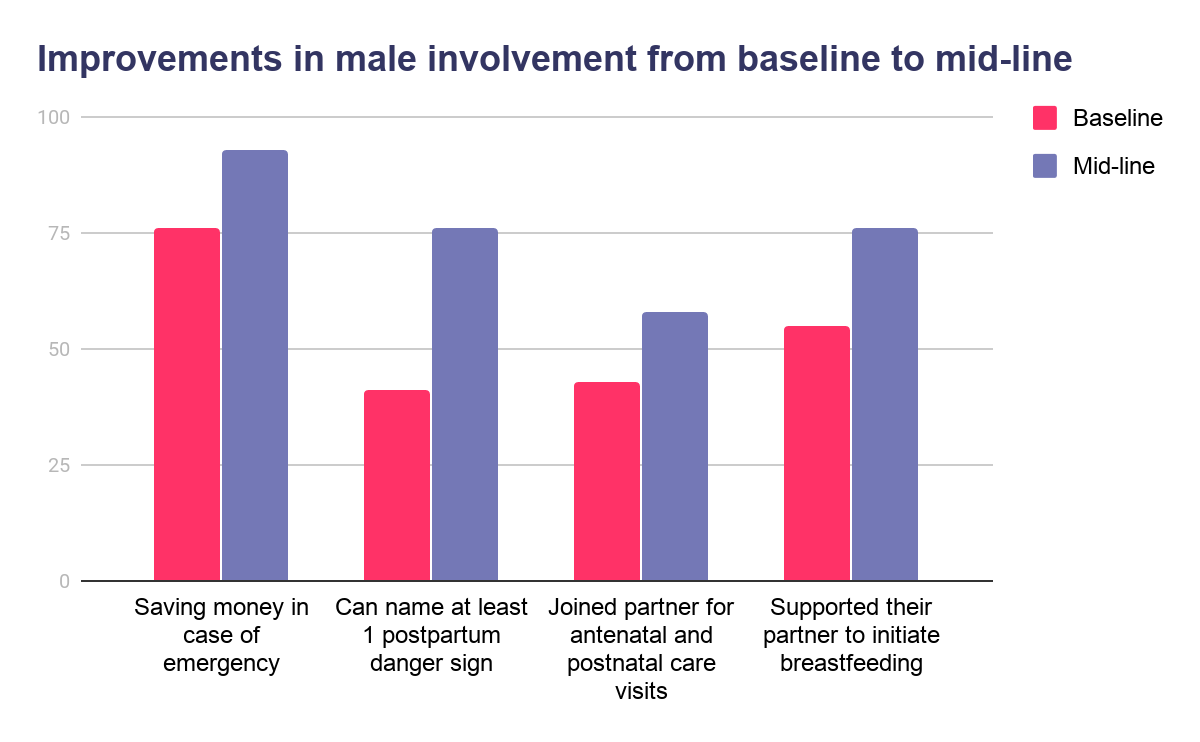

After 8 weeks, we conducted follow-up phone surveys with a sample of 100 users. With the results of the phone survey with users, we compared the knowledge and behaviors of men who had not received the messages. There were some really encouraging differences:

- 93% of men who received the messages reported they had saved money in case an emergency occurred during pregnancy or birth (compared with 76% at baseline)

- 76% of men who received the messages could name at least one danger sign a woman might experience after delivery (compared with 41% at baseline)

- 58% of men who received messages indicated they joined their partner for antenatal and postnatal care visits (compared with 37% at baseline)

- 76% of men who received messages reported supporting their partners in initiating breastfeeding (compared with 55% baseline)

Interestingly, there were some outcomes where we did not observe any changes. For example, the Kenya Ministry of Health guidelines currently state that pregnant women should have 4 or more antenatal care visits, and ~30% of men at both time points indicated they believed a woman needed 3 or fewer visits during pregnancy.

There was also no change in the number of men who said they supported their partners by bathing, burping, or changing diapers for their babies (around 65% at both time points said they engaged in these activities). We recognize that some cultural norms can be difficult to shift with simple text messages.

Adopting a more holistic approach to improve health outcomes

We made some small adjustments to the messages based on feedback and the results from the male user surveys, and launched the male partner program in English and Swahili across the Counties where we work.

We are looking at creative ways to reach men, such as in the places they gather or work, church, online, radio, or through community health structures, because men still need to be informed by their female partner about the free service or attend a clinic visit to enroll.

We hope that by taking a more holistic view of the people involved in maternal and newborn health, we can ensure more correct information is spread and more support is possible for women, infants, and families.