The ‘double burden’ for mothers and newborns in informal settlements

Exposure to air pollution is associated with several adverse outcomes for mothers and babies, including associations with low birthweight, stillbirth, growth restrictions, preterm birth, and other gestational complications (1).

These concerns are of critical importance for residents of informal settlements, where health outcomes are already below the national average, however there is limited data on personal exposure for pregnant women and new mothers.

Identifying and characterising the sources of exposure is key to finding potential solutions for mitigating air pollution exposures for them and their children.

As part of the Kuboresha Afya Mitaani (KAM) project, Jacaranda and Berkeley Air Monitoring Group conducted an air quality study to understand links between the health of women, newborns, and children and the environmental health of their surroundings.

The study aimed to:

- Characterize environments contributing to PM2.5 exposure (1) for mothers in informal settlements.

- Determine which factors are associated with increased exposure to PM2.5 and prospects for mitigating that exposure through interventions.

Characterising the determinants of poor air quality

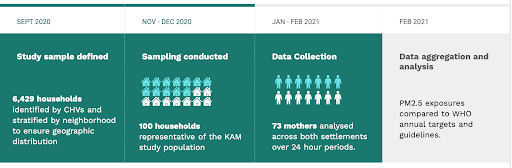

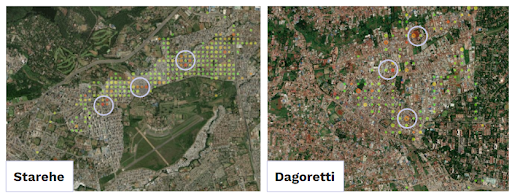

Jacaranda and Berkeley Air ran the air quality study in the two informal settlements between December 2020- February 2021. Eligible study participants were expecting and new mothers aged 15-49 years with babies 0-11 months, living in the selected KAM study villages and expecting to stay in the same location for the next 6 months. Implementation timelines are below.

Jacaranda and Berkeley Air monitored the personal PM2.5 and GPS location for 71 mothers in Mathare and Kawangware.

Participants were outfitted with backpacks to carry the monitoring instruments for 24-hour periods, and ambient PM2.5 monitors were installed in each community. Time-activity surveys were administered to contextualize the PM2.5 and location data with the sources and activities contributing to exposure.

GPS data was used to determine potential pollution hotspots and to categorize the participants’ location as being home vs. away from home.

What we learnt about pollutants in informal settlements

Overall, the mean daily exposure for participants was found to be high (43.9 and 44.5 µg/m3, in Mathare and Kawangware respectively), exceeding the WHO annual target (35 µg/m3).

Several significant findings emerged from the study, as outlined below:

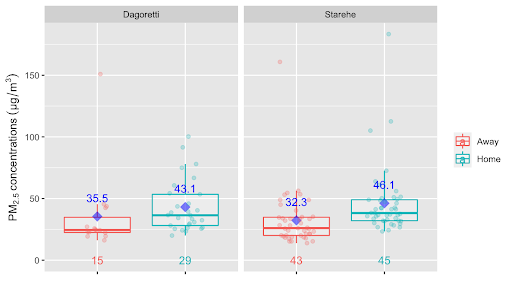

All participants had substantially higher exposure when at home versus away from home.

The GPS data allowed us to categorize ‘at home’ versus ‘away from home’ exposure to better understand potential sources and behavioral patterns that might be contributing to increased exposure. Mothers experienced, on average, 33% greater exposure at home, a surprising result given vehicular combustion and resuspended dust.

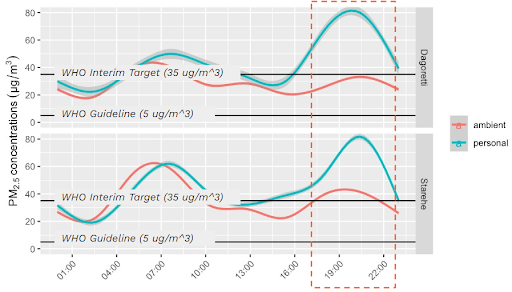

Personal exposures peak during the evening.

The chart right shows a comparison of exposures and ambient concentrations averaged over the course of a day. The exposures generally track ambient concentrations, with the exception of evenings, when personal exposures peak to higher concentrations, suggesting additional sources and/or pronounced behavioural differences during this time.

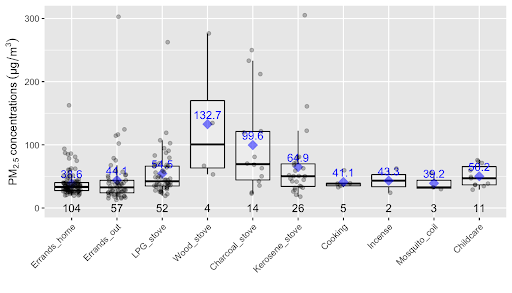

At home, exposures during cooking with wood or charcoal were higher than other activities.

Study participants using solid fuels recorded 48% higher exposures than those who didn’t. Cooking with wood and charcoal was associated with the 2nd and 3rd highest contributions towards personal exposures at 19% and 15%, despite accounting for only about 10% of the exposure sample times.

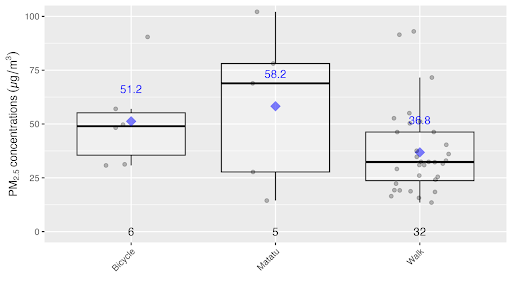

Walking had higher exposures compared to other transportation modes.

Away from home, the mean exposure to air pollution whilst walking was 27% lower than when using a matatu (Kenya’s public minibus service) or riding a bicycle, although the analysis indicated relatively small sample sizes for the latter two modes of transport.

What can other implementers working in urban informal settings learn from this?

While traffic and other ambient sources are certainly impacting PM2.5 exposures across urban environments, the fact that personal exposures averaged at 40% higher than ambient across the settlements suggests the contribution of other sources, like cooking with wood or charcoal.

The results indicate the most promising and practical intervention to reduce exposures would be to transition households to cleaner fuels such as LPG and ethanol, especially given recent evidence to show the cost-effectiveness and availability of electric cookers and innovative Nairobi-based LPG and ethanol programs working to overcome cost and convenience barriers.

Longer-term, lowering exposures will require addressing ambient pollution via government and/or community-backed efforts.

Study data provides evidence that a vulnerable population is being impacted, and is therefore valuable in future advocacy efforts. An Air Quality Action Plan and Act is currently in place in Nairobi, but additional strategic efforts are needed to protect vulnerable communities from acute exposure, including:

- Advocacy efforts to incorporate environmental solutions within MNCH budget allocations

- The use of Multi-stakeholder Forums to ensure a cross-sectoral approach to MNCH interventions.