A woman’s clinical history can inform clinicians about her potential risk during and after pregnancy. Certain high risk conditions in pregnancy have the potential to repeat themselves.

For example, if a woman has preterm labor in her first pregnancy, there is a 25% chance it could occur in a subsequent pregnancy, while 10-15% of women who experience preeclampsia in a prior pregnancy experience it again. Similarly, broader medical disorders can predispose women to a higher risk pregnancy. For instance, women with hypertension are at higher risk of developing preeclampsia.

PROMPTS, Jacaranda’s two-way SMS service, uses AI to screen for current pregnancy and postpartum risk. Today, when a mothers sends a message to PROMPTS, her message is triaged for risk based on the symptoms and experiences she reports. If the AI identifies a danger sign (eg. heavy bleeding), her message is prioritized to a human helpdesk for further support and referral.

However, these high risk pregnancies could be monitored more proactively on the platform by collecting clinical information before a mother’s first message. Last year, Jacaranda trialed a SMS-based approach to clinical risk screening on PROMPTS.

We looked to understand whether clinical history data could effectively be collected through an SMS tool, specifically:

- Whether users were willing to disclose this information to an SMS tool

- What knowledge women had of their medical history, and from what source

- And how to effectively capture and use this information towards more personalized care

Our hope is that by understanding how to use SMS for clinical screening, we can improve the accuracy of how high risk women are triaged by PROMPTS, and further personalize the messages they receive.

Understanding how moms perceive and engage with SMS-based screening

Our exploration was split into two phases. The first phase was designed to understand user perceptions of digital risk screening, and the second phase tested SMS content to feasibly collect this data, as below:

(1) Interviews were conducted with 29 pre and postnatal PROMPTS users in Kilifi, Kitui, Murang’a and Nakuru to determine the acceptability of SMS-based clinical risk screening, including what women knew about their clinical history, and the perceived benefits and barriers to sharing this kind of information with PROMPTS.

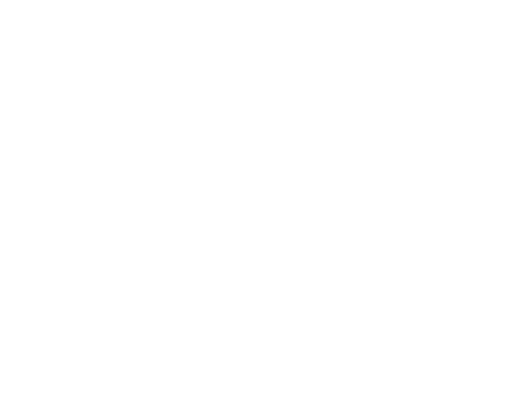

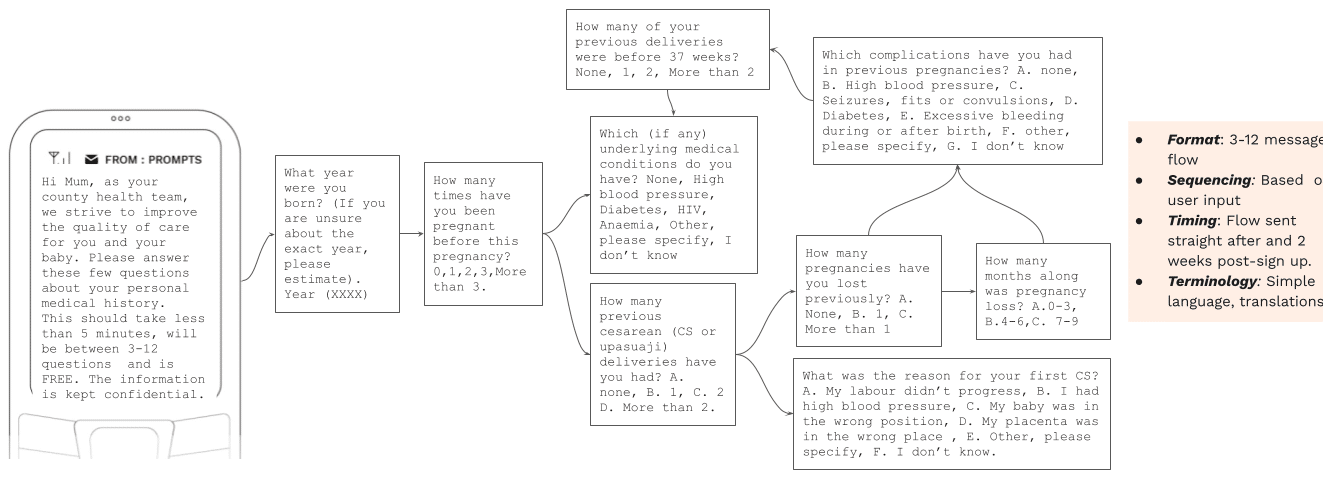

(2) A/B message testing was then introduced to test how to increase trust and engagement with the screening process and capture clinical data via SMS. The content for the messages was based around the most common causes of maternal morbidities /complications during pregnancy, including age, previous complications, and preterm birth, as well as insights from the interviews. The pilot included two rounds of A/B testing with 329 PROMPTS users to track engagement/response rates against different message flows (Figures 1 and 2). Our experience with PROMPTS is that format, sequencing, timing, and terminology influence response rates, and we used these criteria to adapt messages over time.

Learnings and Insights

1. Are women willing to disclose clinical information to an SMS tool?

The interviews revealed a surprising, yet encouraging, insight: women are open and willing to share information about their clinical history with an SMS tool, if they trust the tool and know how the resulting data will be used.

Some respondents reported that sharing clinical information in this way made them feel either heard and empowered, knowing that the information would inform more personalised care and support going forward.

Sharing this information makes me feel more taken care of because I know it will support me in the long term.”

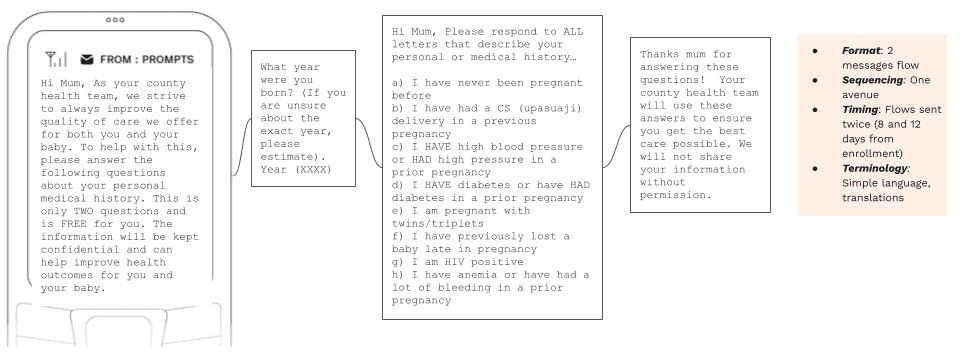

The responses led to some new design considerations (Figure 3) around building trust in the clinical risk screening process and incentivizing engagement, namely:

- White labeling them with the name of the facility or county where they signed up to PROMPTS to build credibility and familiarity. Reminding users in the welcome, or introductory message that responses are free to reduce financial barriers around submitting information to PROMPTS.

- Highlighting how and where the resulting data will be used (ie. informing a more personalized, supportive service and added value in the health system), and a commitment to keeping all information confidential.

- Piloting different hours for sending flows. Women were willing to spend between 5-10 minutes answering questions, but only when they had availability. Evening hours (6-8pm) were suggested as when women were most receptive/ available to answer screening questions.

- Designing targeted messages that are responsive to community influences, given some women felt they needed to notify their husband messages, or rather receive messages through a partner’s phone (despite owning one themselves).

2. What knowledge do women have of their medical history, and from what source?

One question we’re often asked is around the accuracy of this self-reported information – ie. How qualified are users to provide clinically-accurate information and how does this impact the decisions we make off the back of this information?

An initial assumption we had was that most women would have a basic understanding of their clinical history, but lack some clinical specifics about what they’d experienced based on limited access to the right information, or limited contact time with nurses in facilities.

The interviews reinforced this assumption, revealing specific knowledge gaps around certain complications, but strong familiarity with others, as well as the information sources – if any – women drew from to understand their clinical history. Specifically, we learnt that:

- The majority of women understood some complications when described in symptoms, but were unfamiliar with their appropriate medical terms (eg. preeclampsia was broadly recognized as ‘high blood pressure’, ‘postpartum haemorrhage’ as ‘bleeding’, and complications such as stillbirth, preterm labor, and breech delivery were not recognized at all).

- There was a gap in awareness around the risks presented by certain complications, and a lack of information on causes, prevention and outcome of these complications.

- The most commonly-recognized complications included high blood pressure, bleeding during pregnancy, excess bleeding after delivery and severe headaches during pregnancy.

- Major information sources were family and friends by nature of close proximity and trust.

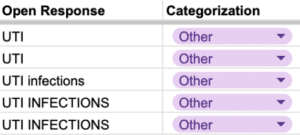

Beyond this, examining the responses to the A/B message testing indicated that pregnancy risk is often understood differently. Open response messages (ie. messages with ‘Other, specify details’ options) revealed knowledge gaps around what constitutes a pregnancy risk. For example, some women reported Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) as a prior risk-related issue (Figure 4), which although technically a complication, doesn’t place a woman at risk during a subsequent pregnancy.

Insights from the interviews and messaging testing prompted further design considerations to increase the likelihood of capturing useful information from women, and our interpretation of the data, including:

- Simplifying screening questions. In some cases, common Swahili words were used to describe procedures (eg. cesarean to ‘upasuaji’, meaning ‘surgery’), while, in others, simplified terminology (eg. ‘haemorrhage’ to ‘lots of blood’, ‘preeclampsia’ to ‘high blood pressure’) increased interpretability.

- Using word variations to describe a risk to increase interpretation and engagement. For instance, using ‘seizure, fit or convulsion’ to describe a seizure.

3. What are the most effective ways to capture clinical information via SMS?

Results from testing the messages reinforce the FGD insights: women are willing to However, reception to the two flows offers key learnings for improving the accuracy, depth and sensitivity of this data capture, as below:

- Short message flows increase engagement without damaging data capture potential. Multi-input message flows lead to responder fatigue. Only 2% of mothers who received the first, extended survey answered all questions. Shorter message flows improved response rates and eliminated drop off (Table 1). Additionally, the shorter flows didn’t necessarily impact their risk screening potential. The % of high risk mothers identified was similar for both flows (between 11-19%), indicating that a concise flow structure yields similar rates of identification for high risk women but at a higher overall number of women.

| Flow | Response Rate (mothers responding to 1+ q in flow) | Drop off Rate (% who didn’t complete all q’s in the flow) | % Mothers identified as high risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow 1 | 25% | 98% | 11.67% |

| Flow 2 | 50% | 0% | 18.93% |

- The timing of when mums receive flows influences engagement. Response rates were highest when screening questions were sent 2 days after enrollment (vs. at enrollment, or 8 or 12 days after), leading to the assumption that women are most receptive to screening when they’ve had a bit of time to familiarize with the platform, while also top of mind soon after enrollment.

Using this data going forward

Effective data collection relies on trust, and trust relies on transparency. Women need to know that they are not being exploited for a data capture exercise, rather that their feedback will benefit them in both the short and long term.

The interviews highlighted that women were willing to share their clinical history if they knew it would deliver added value to their experience on PROMPTS and in the health system, and so an important next step in this work was to explore avenues to personalize support based on the data collected. Some early ideas for this are outlined below.

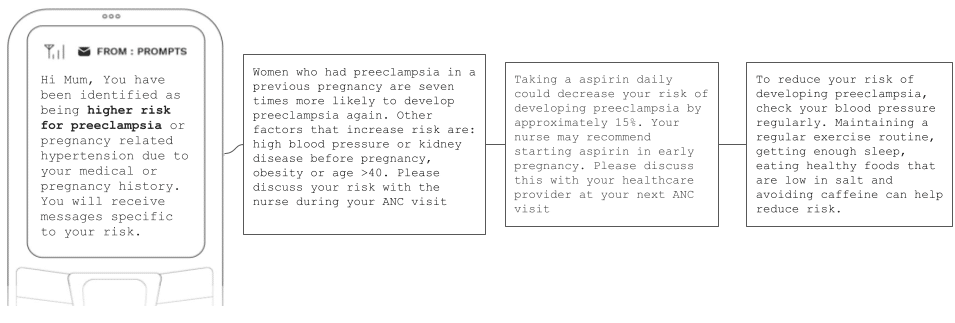

(1) Proactive health messaging to improve knowledge and care seeking behaviors among high risk women. This work supports our understanding of what might categorize a woman as high risk, which presents opportunities to personalize what information she receives to help mitigate increased risk later down the line. We are currently exploring personalized messaging for high risk mothers, based on their medical history. Alongside preeclampsia (Figure 5), messages in the pipeline include tailored information for women who are adolescents, have experienced previous PPH, or carrying multiple pregnancies.

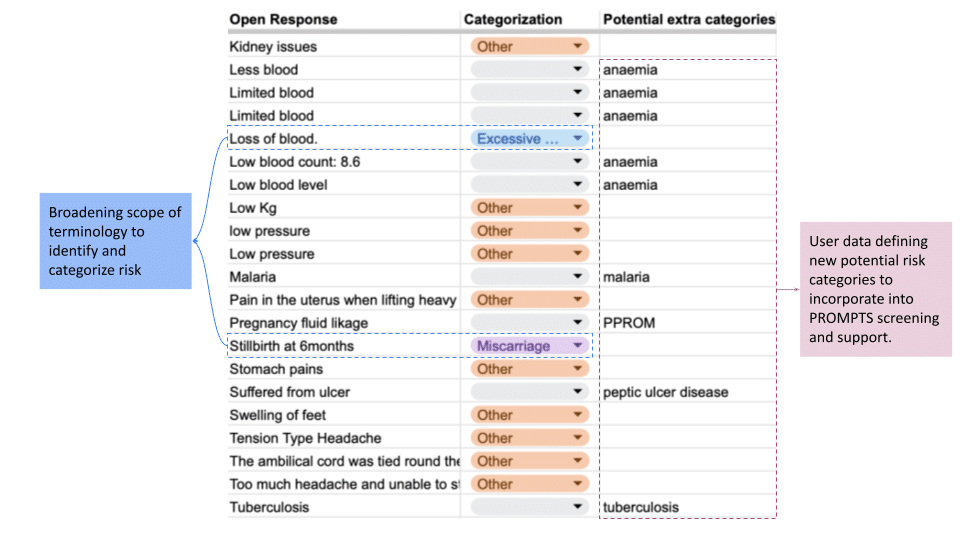

Additionally, open response options (ie. users reporting a complication outside our current seven named risk categories) could help routinely improve or add to tailored messaging flows, as well as our ability to identify risk in conversational data. For instance, mapping a report concerning ‘loss of blood during birth’ against a ‘postpartum hemorrhage’ risk category, or adding new messaging content to support user-reported complications like malaria.

Once we start testing individualized message flows, we intend to monitor changes in health seeking behaviors amongst the subset of pre-identified high-risk women to understand whether these flows increase knowledge and care seeking behaviors.

(2) Faster, more accurate referral based on a mix of clinical and conversational data. Alongside this proactive approach to support high risk mothers, we are also exploring how clinical data can help us be more reactive in identifying potential referral cases.

We can gain a broader window into a woman’s immediate risk by linking her clinical history with her conversational data. For example:

- If an adolescent mother (identified via surveys) sends a message to PROMPTS about contractions, we make the assumption that, due to her age, she is more likely to have a preterm birth. She is automatically moved up the escalation queue and called earlier by our helpdesk, who, by nature of understanding both her past and present risk, can adapt their counseling and referral options.

- Similarly, a woman reporting a history of preeclampsia would not necessarily warrant an escalation, or referral, alone, rather provide the baseline to monitor signs of repeat conditions based on conversational data (eg. a woman reporting severe headaches).

We are still, however, some way off measuring the impact of clinical risk screening on referral outcomes. Our current work focuses on first embedding this clinical and conversational data into the PROMPTS helpdesk, and then training our models and agents to respond to it in the right way.

However, the idea is to continue to hone our ability to predict risk through screening and other methodologies (eg. predictive modeling) before using a cohort study to assess its impact on promoting timely health seeking and receipt of care.

The Last Word

We recognize clinical history is one piece of the puzzle. A complete picture of risk relies on knowing a woman’s past obstetric experiences, her current pregnancy, her underlying medical risk, as well as risk factors deriving from her social, demographic, and environmental circumstances.

Understanding these riks drivers presents a more integrative approach to maternal risk stratification, and the potential to influence a) how PROMPTS understands risk and responds to mothers, b) how mothers understand their risk profile, and c) referral providers act on specific risk profiles. We envision a time in the future where data collection via PROMPTS feeds into a digitized maternal health record, empowering mothers with integrated health information at their fingertips, and streamlining how health information is conveyed between patients and providers.

To read more about what Jacaranda is learning about other maternal risk factors, click through to Jacaranda’s Maternal Risk Series.